|

|

Chapter Six: Down and Out in Australia

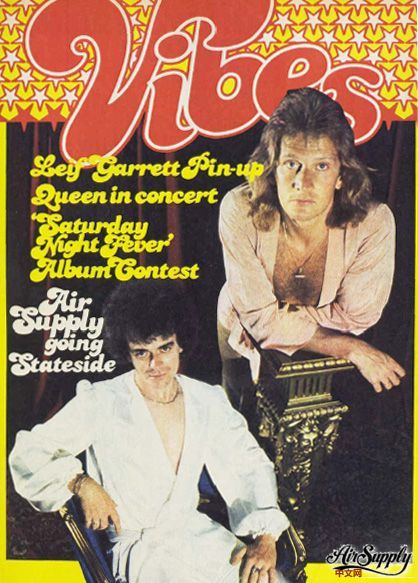

Air Supply arrived back in Australia on December 24, 1977, to a large crowd of fans gathered outside the fence at Sydney Airport’s international terminal. When Air Supply left for the States six months earlier, they consisted of three men and a backing group. They were now two men and a drummer, thanks to the departure of Jeremy Paul and other backing musicians. Guitarist Robin Le Mesurier declined an invitation to join Air Supply after the U.S. tour because he was unwilling to move to Australia.

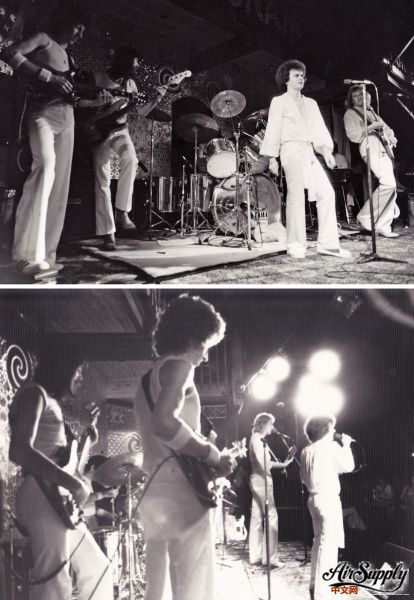

(L-R) Francis, Putt, Macara (drums), Hitchcock, Melick, Russell

Air Supply was not sure how Australian fans would respond to the band’s long absence, but the hoards of people at the airport must have been an encouraging sight. Unfortunately, most of these people did not come to welcome Air Supply. They came to greet Australian band Sherbet, who were arriving at Sydney Airport from South Africa, just four hours after Air Supply. There was no red carpet treatment that other Australian bands got when they returned home, no mass media coverage, almost nothing.

“We came back to Australia thinking we might be the all-conquering heroes,” said Russell. “I think the only people at the airport [for us] were a couple girlfriends and a dog to welcome back the heroes. What Sherbet, Little River Band and all the others did was important for Australian music, and it should have been emphasized that what they were doing were milestones. It hurt when we flew out last year and not too many people seemed to grasp the significance of what we were going to do. Here was an Australian band working on what was the biggest tour in America for 1977. We did 50 dates and the smallest amount of people that we played to at one time was 9,000. What we did was a significant thing.”

The frenetic pace of the North American tour left Air Supply feeling exhausted, and they had little time to rest. Eager to get back in touch with their Australian fans, they auditioned new musicians and rehearsed in mid-January for an eight-week national tour. The touring band included Ken Francis and Tim Gaze on guitar, Bill Putt on bass, Rick Melick on keyboards and Nigel Macara on drums. They played a warm-up leg through the state of Queensland starting on January 27, including a full week in Brisbane. The band sounded great, but the first sign of trouble occurred in Coolangatta, Gold Coast, when Air Supply fired Tim Gaze for arriving late and very drunk to an important soundcheck and rehearsal. Gaze was previously a member of Taman Shud, Ariel and the Tim Gaze Band, and was considered an extremely gifted guitar player. Certainly not the type of musician to let go without careful consideration.

“For the second time in his career, Nigel Macara, bless ‘em, put me up for a gig, this time with Air Supply,” said Tim Gaze. “I flew to Sydney, did the rehearsals, and what do you know, the first gig is at the Jet Club in Coolangatta, my mate Bolton’s old stomping ground. Well, I won’t go into what occurred backstage after the show, but suffice to say, the next morning I arrived back at the Jet Club, an hour late for a rehearsal, and was not unkindly advised that my services would no longer be required on this tour, and here was a gig’s pay, and my airfare back to Sydney.”

National Hotel, Brisbane - Feb 1, 1978 (Ken Francis)

Ken Francis, the youngest member of the band at 24, took over lead guitar duties. Francis joined the tour after his friend Rex Goh got him an audition. “I was repairing guitars and playing for not much in bands with talented but low-paying friends,” said Francis. “Rex had done the U.S. tour with [Air Supply] and had had enough, so he rang me and said ‘You wanna gig?’ I knew Rick Melick, who I think had already been offered the keyboard chair in the band. The audition was intimidating, because already chosen was Bill Putt, who was a legend in my book. Then the other guitarist being auditioned (Tim Gaze) was one of my all-time hero’s from when I’d first seen him with an extremely bohemian surf band called Tamam Shud. It was exciting to go touring again, and this was with a band that had a recent hit. So the vibe was up as we might say back then. The music was a bit ‘nice’ for my tastes. Still, the band was good! Everyone knew what to do and we rocked as hard as Graham would let us.”

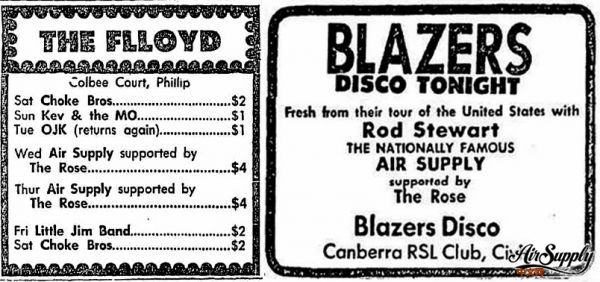

“The first thing was to play to people,” explained Russell. “We preferred a concert situation but we couldn’t do it. Because we were away for so long, we had to do the pubs and rock clubs. But we were rockier than before we went to America so we enjoyed some of the pubs. It was a good change to be able to see the audiences again, but we certainly were spoiled on the Rod Stewart tour. Nothing ever went wrong, everything was always laid on...”

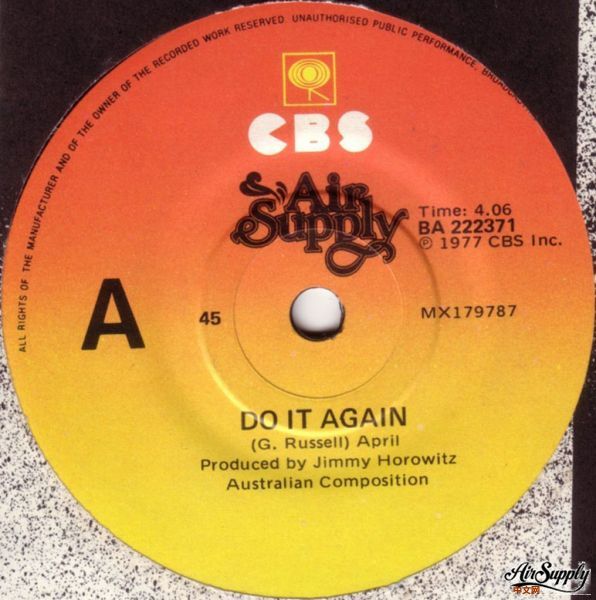

The tour continued through New South Wales and Victoria in February and early March, but concert promoters began pulling out after hearing of the scarce crowds. According to Russell, the tour at that point had drawn only “a thousand people in more than twenty shows.” To add insult to injury, ‘Love and Other Bruises’ was off to a disastrous start in America, and their latest Australian single, the Jimmy Horowitz produced version of ‘Do It Again,’ failed to chart. “It was incredible,” said Russell. “It was soul-destroying. We put out a single [in February], a good single, and it sold four hundred copies. It was the second-best single we had released, [but] the press was mad at us, saying, ‘We’ve been deserted.’ We had seen this kind of backlash happen to other bands who were big here, then left, and came back to a lot of negativity.”

'Do It Again' - Australian Single

The members of Air Supply grew increasingly frustrated with the angry pub crowds. Fans in small country towns were not always respectful of Countdown’s pretty boy icons. Sherbet and Hush were both selling thousands of records throughout Australia, but like Air Supply, they came under attack in the Aussie pubs. Many bands were forced to tour with at least three roadies to help with protection. Suburban pubs were often a gathering place for Sharpies, a violent youth gang found prominently in Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. “We got to a point where you got that loneliness feeling, like the times you’re locked up in the hotel room,” said Darryl Braithwaite of Sherbet. “You had to stay in the room. If you went into town you would come under all sorts of violence, and people yelling at you.”

It was difficult for Air Supply to remain positive at this point in the tour, and friction within the band ensued. When they had arrived in Queensland at the start of the tour, they were welcomed by the sight of guys beating up woman outside a gig at Ipswich. The hostilities would often spill over into the pub, where Air Supply had the unenviable task of entertaining a bunch of violent drunks. To complicate matters, Russell had developed a throat infection very early in the tour, something that he said “happens every time in Queensland.”

To keep the tour alive, the tour manager gave the backing musicians a choice - either carry and set up the band’s equipment themselves so they could cut several road crew, or take a cut in pay. The musicians reluctantly accepted a cut in pay, and Air Supply kept on into the next leg of the tour in Perth and Adelaide. But when the backing musicians arrived at their downtown hotel in Perth, they discovered that their rooms had badly stained linens and no doors behind which to lock up their instruments and equipment. Furthermore, the band members became even more frustrated when they learned that Graham, Russell and Fred Bestall had checked into a classier hotel next to a river and park. After a minor band revolt, the backing musicians found themselves moved into the same hotel as Graham and Russell.

The Flloyd - Feb. 8-9, 1978 Blazers Disco - Feb. 10, 1978

The disgruntled band members stayed on for the rest of the tour, but the frequency of gigs declined, and it was obvious that Air Supply’s music and image could not survive in the Aussie pub scene. The tour ended prematurely following an outdoor show in Adelaide. The bands management team was partly to blame for the failed tour. “The lack of publicity for the tour was woeful,” says Ken Francis, “and I think it’s fair to say that some of the venues we played were bad choices and probably set up the tour’s bad reputation for poor audiences - there were other places the band could have played with audiences more likely to warm to the MOR style. It just became more and more clear that we weren’t getting a great response. I knew all of the bands that Bill Putt and Nigel Macara had played with, and I’d been in some seriously great rock/indie unknowns, and Graham and Russell’s music just didn’t liftoff the way a great band can.”

Russell believed that the two months in Australia following the North American tour were the worst two months in the entire career of Air Supply; “The Australian tour was a shambles. Unprepared. Wrong venues. Wrong advertising. It was a bummer. It was a great shame that any act had to go through such crap....and badly organized crap. It was a tough audience for us because obviously the first hit for us was ‘Love And Other Bruises,’ which was a ballad. And then you’ve got two guys out there that wore what looked like pajamas, and my afro was huge. We copped a lot of grief from the audiences. We went to Queensland to play a couple shows and there was six of us in one hotel room. We arrived late at night after driving there in a Kombi, and had to wake-up the lady at the front desk. We went to the room and it was full of cockroaches. But we had a great voice so we just said that we would do it because that’s what we were made to do.”

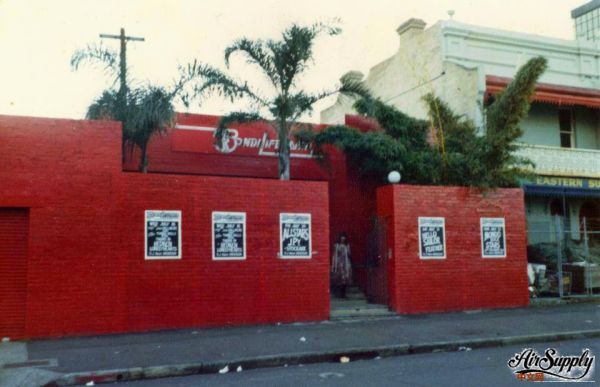

A music critic covering Air Supply’s performance at The Bondi Lifesaver in Sydney wrote:

They still dress in white, their band is rockier, their forte is still harmony vocals with Russell’s high clear range still capable of causing a sweet ache in the sensitive heart. The only trouble is, the punters at the Lifesaver seem to think these boys are a bit pansy or something and the reaction is stiflingly oppressive. And for the skills Air Supply have to offer, they deserve something different to this. It’s no real surprise when the group gives an interview a week later in which it’s claimed they’re pulling up stakes and leaving Oz for ‘as long as possible.’ There’s absolutely no shame playing music for engaged couples (and other romantics) but it is a shame to put it in front of rock ‘n’ roll punch drunks. There’s obviously something wrong with the Oz Music biz when a band like Air Supply has to appear there. - Anthony O’Grady, RAM

The Bondi Lifesaver - Sydney

“We used to open for AC/DC at The Bondi Lifesaver, which I think is the longest bar in the world,” said Graham. “AC/DC used to pack that place out to the rafters. There was probably about four or five thousand people in this pub. We would open and think, ‘Oh my God. They are going to kill us!’ We were freaking out because we were nowhere near as loud as they were. We wore white suits, and sang love songs. AC/DC would come on and just take over. But doing these kind of shows really gave us strength. Angus and the guys would come backstage and tell us how happy they were to have us. It built character, which we needed later when we came to the rest of the world.”

Australian bassist Bill Putt was introduced to Air Supply during the Rod Stewart tour in North America, and he remembers how bad things got for the band. “I was in America [in 1977] and bumped into them,” said Putt. “They said, ‘When we go home to Australia, do you want to play bass?’ And I went ‘aaa-ooo-eeer-alright.’ I knew it was only a three-month thing and it turned out to be a few weeks less than that, so I actually had a good time. They were lovely guys. At this time [Air Supply] was doing really bad. In fact, at one point the little guy, Russell, asked when we finished this tour, if he could sing harmonies in the band that Michael [Rudd] and I ended up having after the Air Supply thing. He was that desperate for money. And we said, ‘No, you’re too short, go away.’”

“It’s been an unfortunate situation in many ways,” said Russell. “It’s always been a cart before the horse situation from the start. The first single became a hit in Australia, so we had to get a band together. Then we did the Rod Stewart tour here and were suddenly thrown into a situation where we had to go to America - there was never a situation like that for an Australian band before, a chance to play before over half a million people and get paid for it. But then there was no chance of extending our stay there, we had visas for a certain period and that was it. We know by leaving when we had to, any situation we’d built up over there would have to subside a little. But then while we were over there some of the thing we’d built up here faded... it’s really a limbo situation at the moment. Lots of people have said to me, ‘You should go out and sing ‘My Way’ and ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ and make a thousand dollars a week.’ And I’m pretty sure I could do that. But I don’t want to. I want to do this. I want to sing Graham’s songs and if I can do that and lots of people like it, then that’s fantastic!”

Air Supply was not the only Australian band that struggled at home during this period. 1978 was the worst year since 1968 for the number of Australian singles in the top 100 (only nine) and likewise for albums (only nine). When Dragon’s ‘Are You Old Enough’ hit #1 in October it became the first local #1 for 17 months, and was only #14 on the overall annual singles chart. Ironically 1978 was the year when Australian recordings truly came of age on the world’s charts. In September, there were two Australian singles in the U.S. Top 10, an incredible achievement by any standard.

Woman's Weekly Magazine - April,1978

Graham moved into a motel in Adelaide following the Australian tour, and met up with new backing musicians in April for a week of shows at the Adelaide Old Mariner. This was to be Air Supply’s last Australian dates before heading overseas again. They planned to race off to a couple concerts in Bangkok at the end of the month, followed by a promotional tour of Japan. They hoped to re-release Columbia’s ‘Love and Other Bruises’ album now that the group was better known and the record would come out in the middle of the year instead of, as last time, Christmas when everyone was releasing records. There was talk about perhaps going out on tour again with Rod Stewart, this time through Britain and the European continent. “Nothing’s definite yet, but we’ve got our fingers crossed,” said Graham. “It would be fantastic for us because Britain is very hard to crack. But if you do, it’s a great springboard.”

Graham moved to a cottage in Adelaide Hills, a popular wine region east of the city of Adelaide. He stayed there for six months writing songs for the next Air Supply album, which was to be recorded in Los Angeles in July. They planned a low profile tour of American campuses to promote the album, and to reestablish their name in that country. It seemed that Air Supply’s future was now in Los Angeles, where Peter Dawkins and his family were now living. “I did most of my writing in Adelaide,” said Graham. “It just seemed to have the right atmosphere. The Adelaide Hills has to be one of the most peaceful areas I know. I went up into the hills with a tape recorder, and sat in a field, and the songs just came. But there was almost no choice but to move to L.A. Even though it was expensive, it was the music center of the world. In Australia you could hit yourself against a brick wall. You could only go so far.”

Shortly before Air Supply was to visit Thailand and Japan, their recording contract with CBS was mutually terminated. There were no nasty legal battles. CBS Australia was not happy with the direction of the band (Air Supply wanted to record more upbeat music), and Air Supply was not happy with the growing debt to their label. “The split with CBS was fairly amicable, and primarily came about because we just didn’t have the support we needed,” said Russell. “There were little things niggling us about the company, and things about us were niggling them. We were the first to admit we blew it. We left too many things for people to do which just weren’t done, but we learned from our mistakes.”

Almost every record deal with a major label at that time stipulated that the label would recover its costs for all recordings made by the artist from all artist royalties. If an artist released multiple albums and only the last one was successful, no royalties would be paid to the artist until the recording cost for all albums had been recouped from the royalties earned on the successful album. Despite having a gold album, the mechanical (records sold) royalties paid to Air Supply for their first three albums would have been minimal at best. A popular saying in the music industry at the time was, ‘a hit single in Australia only pays for your next single.’ CBS figured that because the American album hadn’t broken Air Supply in America, they were never going to make it there. Plus, it was common practice for label’s to free artist’s from their contract so that the label could write off the debt that the artist owed them.

Fact is folks, things aren’t going too well for your local grass roots industry at the moment. Over the past year, three or four new independent record companies have opened, only to close soon afterwards. Or be bought by a major record company. As for live work - well a director of Premier Artists the largest booking agency in Oz, admits the main work place, the Melbourne pubs, have definitely seen their glory days. Then again the controller of a major studio explains an interesting problem:

“To record an album so the sound will stand up to what’s coming in from overseas you have to spend between $8,000 and $12,000 at least. And record companies are saying, ‘but the only guaranteed release market we have is Australia, and to make a profit on $8,000 to $12,000 we have to guarantee the album goes platinum. And very few Australian albums sell those 50,000 copies to make platinum.’” - Anthony O'Grady, RAM

With no record contract and an uncertain future, Air Supply found themselves having to start all over. Graham returned to England where his wife Linda and his kids were now living, after having moved there during the Air Supply/Rod Stewart North American tour. The responsibilities of parenthood made it difficult for Graham to remain in Australia. To make ends meet he hoped to find work as an in-house writer for a music publisher (Riva Music Ltd.), and also finish a rock opera, Sherwood, he was writing about Robin Hood. “I sold everything I had in Australia,” said Graham, “but it was great to be back in England and to see the kids again. It was around 1975 when I began dreaming of the greenwood in musical terms, and feeling a renewed pride in being from Robin Hood country. Then I had a brainstorm, I should write some songs that tell the story of Robin and all of his adventures and call it Sherwood. At the same time, I entered Jesus Christ Superstar and during the show, began to realize how a show called Sherwood could be staged.”

Russell took on several jobs in Australia. One of those involved working with his friend, filmmaker Chris Lofven, in a Melbourne-based film production company called VTC (Videotape Corporation) that specialized in rock clips. Lofven had filmed music clips for many Australian acts, such as Daddy Cool, Split Enz, Spectrum, Mother Goose, and Skyhooks. The Little River Band, a successful Australian group, were shooting a music video for their hit song ‘Reminiscing,’ when Russell was sent out to buy the group sandwiches. “It was the most humiliating experience of my life,” he said. “I knew someone should be going out and getting us sandwiches.” Russell also worked as a studio singer, doing commercials for Maxwell House, Coke and American Express, but he made very little money because the commercials paid a flat fee rather than a royalty for each airing. He was forced to settle for a fee of $120 for the Coke advertisement. To make ends meet, Russell reluctantly moved into his parents home in Melbourne.

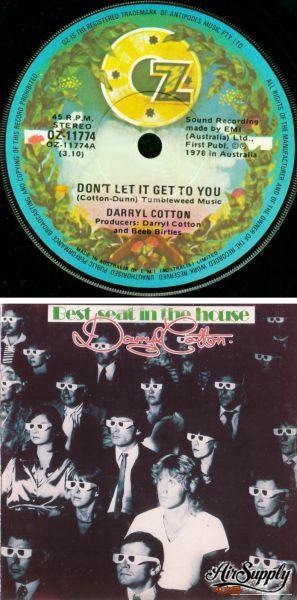

Darryl Cotton LP & Single

Desperate for money, and wanting to stay involved in the music business, Russell sang backup vocals on a record by Australian Darryl Cotton. Cotton was a member of Australian band Zoot, who broke up in 1972. After five years in America, trying to make it as a singer and actor, Cotton returned to Australia to launch a solo career. He assembled a who’s who of Australian music to record the album, including members of Sherbet, the Little River Band, John Paul Young’s band, and Russell Hitchcock of Air Supply. Russell sang harmonies and backup on 8 of the 11 tracks. His higher pitched vocals helped shape the overall sound on the album, especially the track, ‘Don’t Let It Get To You,’ which was released as a promotional single in August, 1978. Two months later, it reached #22 on the Melbourne charts.

Darryl Cotton’s album, ‘Best Seat in the House,’ took two years to complete and was released in April, 1980. The second single, ‘Same Old Girl,’ was a national Top 30, and Top 10 on 2WS music chart. The song earned Cotton a Countdown award for Best Solo Male Performance in 1980, exactly ten years after his former band Zoot won the same award for a group. ‘Here Comes Another Heartache’ was the third single and it received significant airplay in parts of Australia. “Russell sang most of the harmonies on the album with me,” said Cotton. “Getting around to doing the album took a year and a bit, but the actual recording was done in two weeks.” Russell’s involvement on the record was no doubt a humbling experience. He was, after all, the owner of a gold certified album in Australia, and was now reduced to singing backup as a session musician.

Air Supply believed that perhaps they would be better off as a trio once again, so they asked Darryl Cotton to join the band. “It was interesting,” said Cotton, “because after that [‘Best Seat In The House’] session, Russell and I got on really well, and he called me up a couple of days later and said, ‘I’m in this band and we are about to release our first single in America. We were wandering if you would like to join?’ I said, ‘Look, I’ve just come back from America. I really appreciate it, and I wish you well.’ But I said no to joining Air Supply. I liked [Russell] a lot. We got along really well, and our harmonies blended and everything. I had heard ‘Love and Other Bruises’ by Air Supply, and it had a good chance in America. It had that middle-of-the-road American style. But I said no, and the rest is history. I wouldn’t have had my beautiful daughter, my wonderful son and my wife. That was destiny.”

“We did talk about [adding Darryl Cotton] to Air Supply,” said Graham. “It would have changed everything because he had such a great voice. We had known him for a long time and had seen him play with Zoot. But he didn’t think it was his thing. He wanted to have his own career. But if he had joined, it would have been incredible because that third voice would have been fantastic. We have seen Darryl over the years and have joked with him about that.”

Graham and Linda divorced after 11 years of marriage. Graham’s prolonged absence made it difficult to maintain a healthy relationship, especially after the six months in North America with Rod Stewart. “I always knew that if the opportunity came,” said Graham, “I wasn’t going to let it slip away. Both of my children were very young and I had to go for six months. It was very difficult. That was the sacrifice that I had to make, and I made it knowing very well that [divorce] might be the outcome.”

Graham returned to Australia and escaped to his motel in Adelaide for some much needed rest, and more importantly, revive Air Supply. He wrote new songs, perhaps inspired by his friend, Chrissie, who lived close by. They eventually moved in together. Graham remembers the night he wrote a song that would change his fortune. “I took six months off in Adelaide and I was living with Chrissie,” he said. “When I’m not busy or working I get a bit strange, cause I get jittery. Well, I got a bit jittery and got into an argument that night, and I walked out,’ cause I don’t like arguing. So I walked around, came back and wrote ‘Lost In Love.’ Because that’s how I felt.”

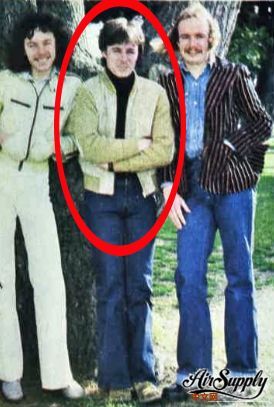

Brian Hamilton (Right)

While still in Adelaide, Graham found two new band members in bassist Brian Hamilton and lead guitarist David Moyse, who were once members of the Adelaide-based group The Jules Funk Band. They both also performed on the 1974 self-titled album from Adelaide-based singer-songwriter David Ninnes. Brian Hamilton joined Graham and Russell up front, taking the spot offered to Darryl Cotton. Also joining the band was 28-year-old Australian drummer Ralph Cooper, who was a member of the critically acclaimed symphonic rock band Windchase. Due to financial reasons, Windchase decided in October, 1977, that it was not worth keeping the band together on the road. They had just completed an unsuccessful tour of Australia, and their single, ‘Glad To be Alive,’ did poorly on radio. The band members believed they could make more money playing in other bands. “It got to a place where originally there were three guys, Russell, Graham and Jeremy Paul, plus a backing band,” said Ralph Cooper. “Then they wanted to become a real group, so I came along. They seemed to like what I was doing, and I liked what I heard. With my background, I was coming from jazz, rock and roll and country, and I had an ear for all things good. Air Supply sounded good to me.”

Windchase - R. Cooper

Before parting company with CBS, Graham had planned on finding new band members in America. “We decided it would be just as easy to find the right people here,” said Graham, “and mold the outfit so we would be ready to hit the road as soon as we arrived [in America]. For the past month, we’ve been flat out rehearsing, getting tracks organized for the new album. At the moment, this is the most important thing to us. We’re rockier than before, and I think a lot better. The music is progressing quite quickly as we get to know each other better. We’re putting new things in all the time. The music we’re recording now is not blatant commercial music like it has been in the past. ‘Love And Other Bruises’ was just blatant commercialism and although it was a great song, we manufactured it for the market. But now we’re putting more emphasis on the feel of the music. And we’re hoping that people are going to slot into the feel that it has for us.”

Despite continued interest from Billy Gaff, who was visiting Australia with his latest act John Cougar, it was not known on what label the next Air Supply album would be released. Gaff took working tracks from the album back to the States. Meanwhile, Air Supply couldn’t afford to be on the road because they were down to playing for $200 to $300 a night, and there were seven people in the band. David Moyse, who agreed to a retainer of $100 a week, contemplated leaving the band on several occasions. Russell phoned Graham to say he was not sure how much longer he could continue in the band. Graham explained that he had written new material, and that he needed Russell to come to Adelaide with a couple of the guys from the band. Russell got on a bus and made the 16 hour drive from Sydney to Adelaide, where Graham played him ‘Lost In Love’ on his acoustic guitar. Before he had finished, Russell knew they had something special. “This is a hit,” he said, “and this is going to put us in business worldwide.” |

|